A customer called us, quite upset, because their RavenDB cluster was failing every few minutes. That was weird, because they were running on our cloud offering, so we had full access to the metrics, and we saw absolutely no problem on our end.

During the call, it turned out that every now and then, but almost always immediately after a new deployment, RavenDB would fail some requests. On a fairly consistent basis, we could see two failures and a retry that was finally successful.

Okay, so at least there is no user visible impact, but this was still super strange to see. On the backend, we couldn’t see any reason why we would get those sort of errors.

Looking at the failure stack, we narrowed things down to an async operation that was invoked via DataDog. Our suspicions were focused on this being an error in the async machinery customization that DataDog uses for adding non-invasive monitoring.

We created a custom build for the user that they could test and waited to get the results from their environment. Trying to reproduce this locally using DataDog integration didn’t raise any flags.

The good thing was that we did find a smoking gun, a violation of the natural order and invariant breaking behavior.

The not so good news was that it was in our own code. At least that meant that we could fix this.

Let’s see if I can explain what is going on. The customer was using a custom configuration: FastestNode. This is used to find the nearest / least loaded node in the cluster and operate from it.

How does RavenDB know which is the fastest node? That is kind of hard to answer, after all. It checks.

Every now and then, RavenDB replicates a read request to all nodes in the cluster. Something like this:

The idea is that we send the request to all the nodes, and wait for the first one to arrive. Since this is the same request, all servers will do the same amount of work, and we’ll find the fastest node from our perspective.

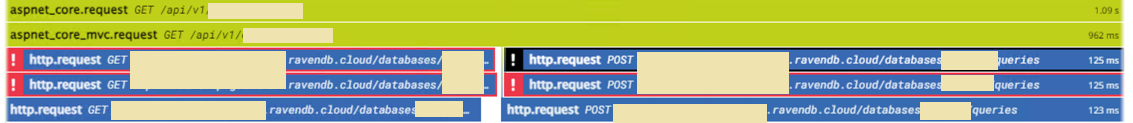

Did you notice the cancellation token in there? When we return from this function, we cancel the existing requests. Here is what this looks like from the monitoring perspective:

This looks exactly like every few minutes, we have a couple of failures (and failover) in the system and was quite confusing until we figured out exactly what was going on.

_thumb.png)