Reviewing SledPart II

The first part is here. As a reminder, Sled is an embedded database engine written in Rust. It takes a very different approach for how to store data, which I’m really excited to see. And with that, let’s be about it. In stopped in my last post when getting to the flusher, which simply sleep and call flush on the iobufs.

The next file is iobuf.rs.

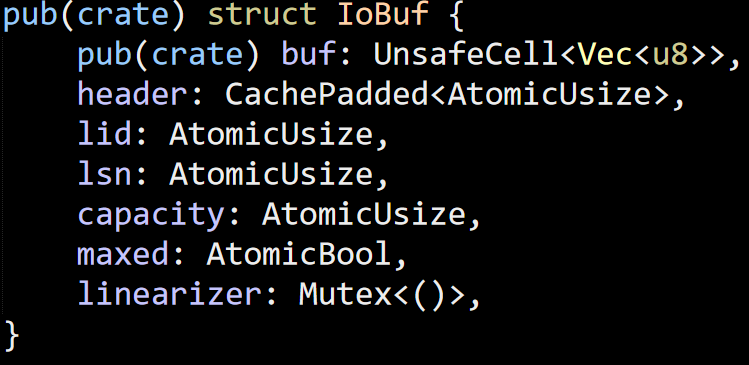

Note that there are actually two separate things here, we have the IoBuf struct:

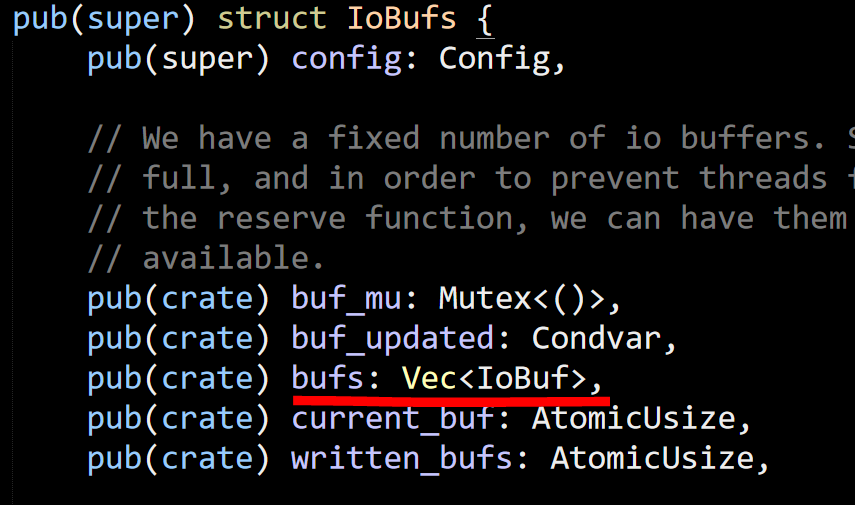

And we have IoBufs struct, which contains the single buffer.

Personally, I would use a different name, because is is going to be very easy to confuse them. At any rate, this looks like this is an important piece, so let’s see what is going on in there.

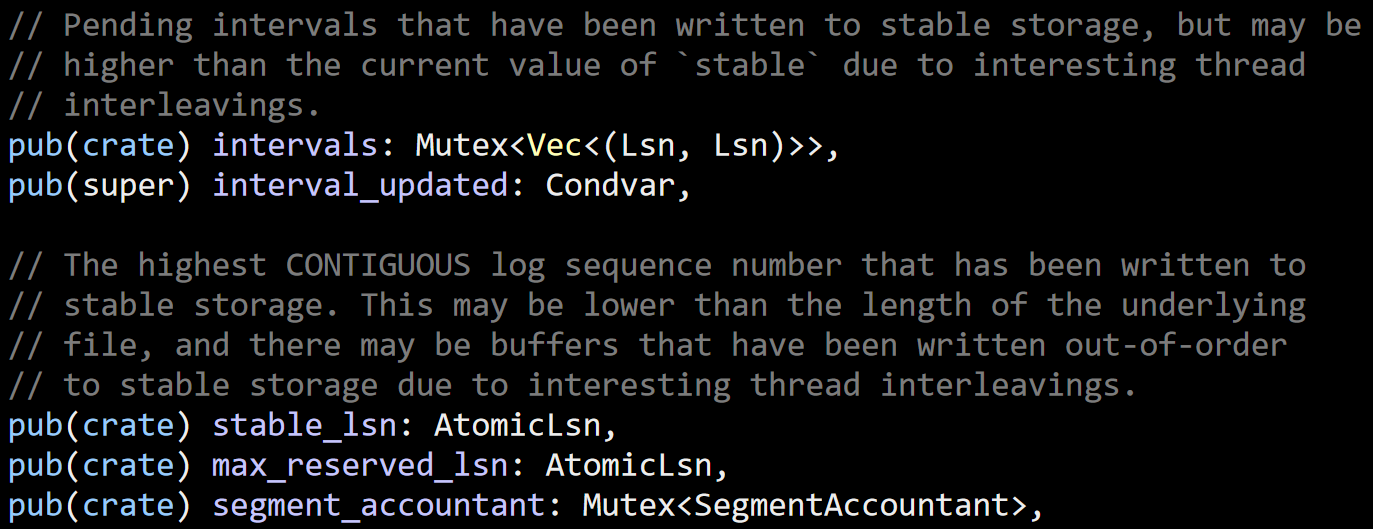

You can see that the last three fields shown compose of what looks like a ring buffer implementation. Next, we have this guys:

Both of them looks interesting / scary. I can’t tell yet what they are doing, but the “interesting thread interleaving” stuff is indication that this is likely to be complex.

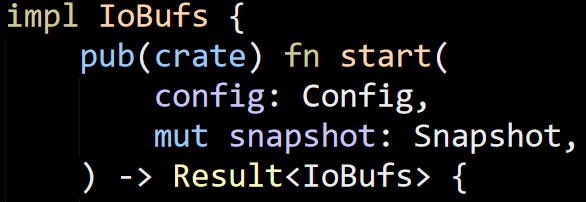

The fun starts at the start() function:

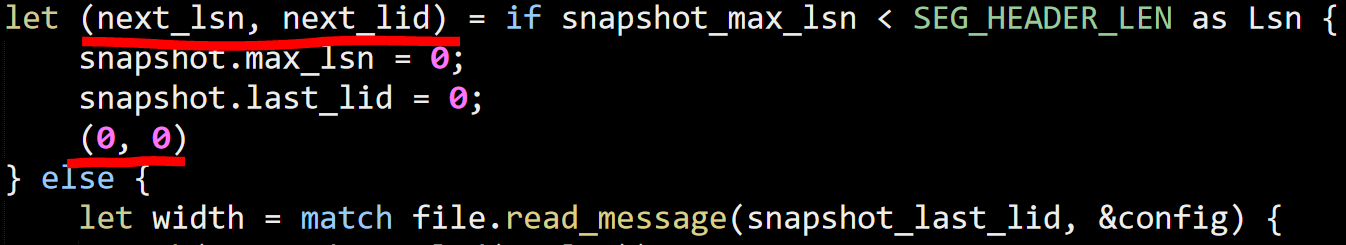

This looks like it is used in the recovery process, so whenever you are restarting the instance. The code inside is dense, take a look at this:

This test to see if the snapshot provided is big enough to be considered stand alone (I think). You can see that we set the next_lsn (logical sequence number) and next_lid (last id? logical id?, not sure here). So far, so good. But all of that is a single expression, and it goes for 25 lines.

The end of the else clause also return a value, which is computed from the result of reading the file. It works, it is elegant but it takes a bit of time to decompose.

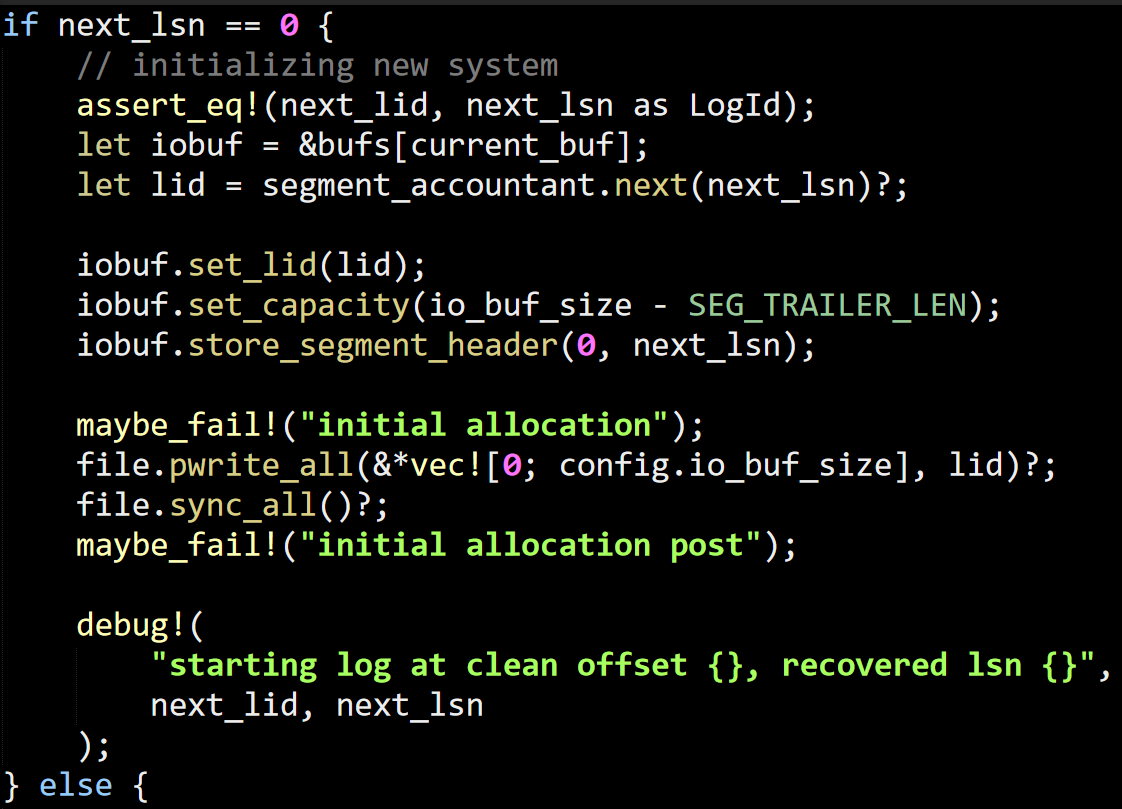

There is something called SegmentAccountant that I’m ignoring for now because we finally got to the good parts, where actual file I/O is being performed. Focusing on the new system startup, which is often much simpler, we have:

You can see that we make some writes (not sure what is being written yet) and then sync it. the maybe_fail! stuff is manual injection of faults, which is really nice to see. The else portion is also interesting.

This is when we can still write to the existing snapshot, I guess. And this limits the current buffer to the limits of the buffer size. From context, lid looks like the global value across files, but I’m not sure yet.

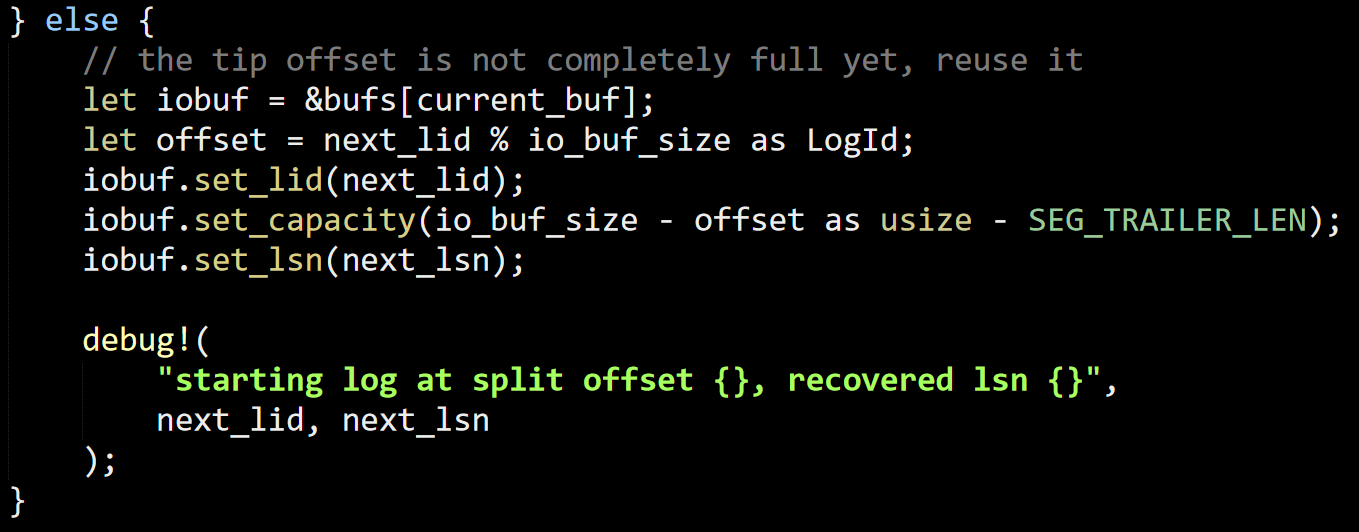

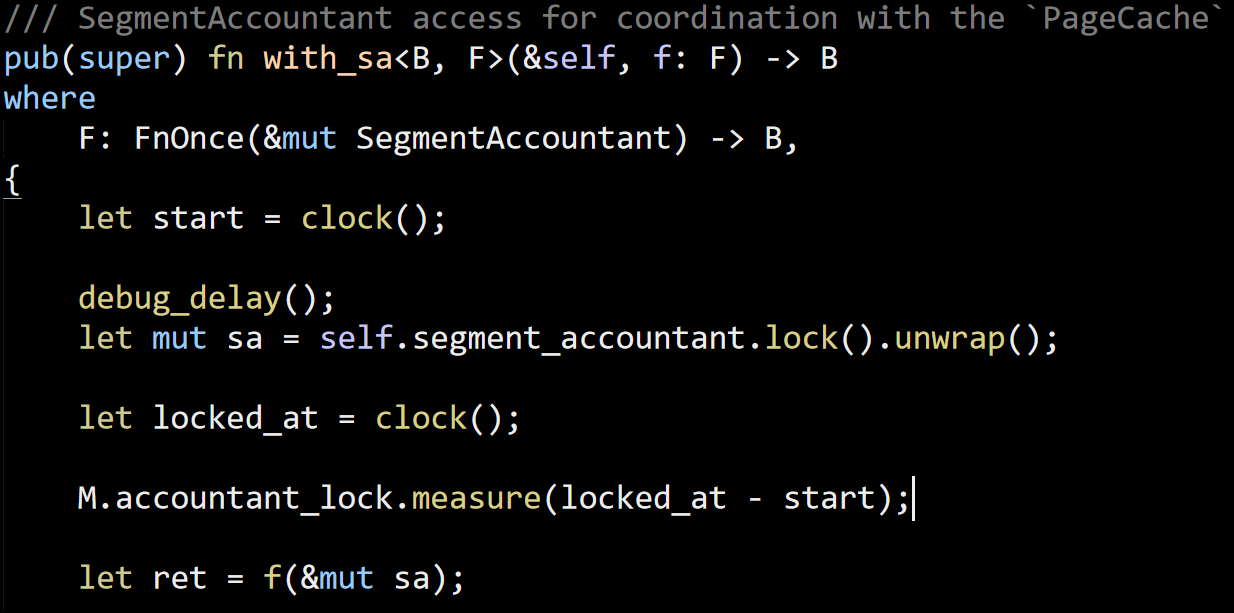

I run into this function next:

On its own, it isn’t really that interesting. I guess that I don’t like the unwrap call, but I get why it is there. It would significantly complicate the code if you had to handle failures from both the passed function and with_sa unable to take the lock (and that should only be the case if a thread panicked while holding the mutex, which presumably kill the whole process).

Sled calls itself alpha software, but given the number of scaffolding that I have seen so far (event log, debug_delay and not the measurements for lock durations) it has a lot of work done around actually making sure that you have the required facilities to support it. Looking at the code history, it is a two years old project, so there has been time for it to grow.

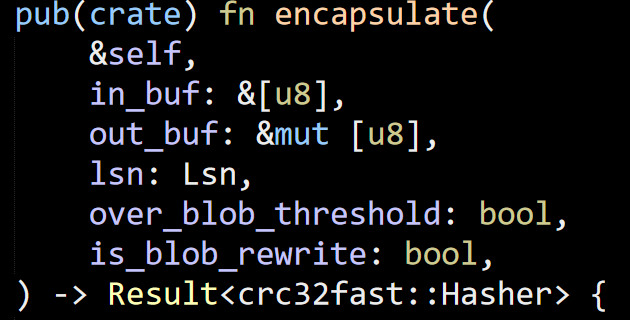

Next we have this method:

What this method actually going on in here is that based on the size of the in_buf, it will write it to a separate blob (using the lsn as the file name). If the value is stored externally, then it creates a message header that points to that location. Otherwise, it creates a header that encodes the length of the in_buf and returns adds that to the out_buf. I don’t like the fact that this method get passed the two bool variables. The threshold decision should probably be done inside the method and not outside. The term encapsulate is also not the best choice here. write_msg_to_output would probably more accurate.

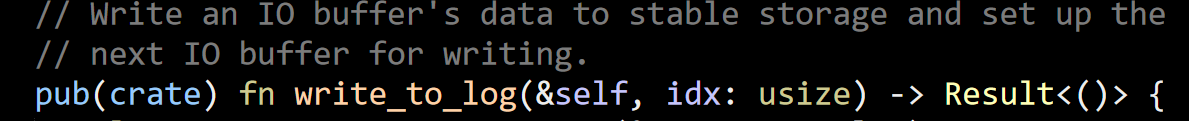

The next interesting bit is write_to_log(), which goes on for about 200 lines. This takes the specified buffer, pad it if needed and write it to the file. It looks like it all goes to the same file, so I wonder how it deals with space recovery, but I’ll find it later. I’m also wondering why this is called a log, because it doesn’t look like a WAL system to me at this point. It does call fsync on the file after the write, though. There is also some segment behavior here, but I’m used to seeing that on different files, not all in the same one.

It seems that this method can be called concurrently on different buffers. There is some explicit handling for that, but I have to wonder about the overall efficiency of doing that. Random I/O and especially the issuance of parallel fsyncs, are likely not going to lead to the best system perf.

Is where the concurrent and possibly out of order write notifications are going. This remembers all the previous notifications and if there is a gap, will wait until the gap has been filled before it will notify interested parties that the data has been persisted to disk.

Because I’m reading the code in a lexical order, rather than in a more reasonable layered or functional approach, this gives me a pretty skewed understanding of the code until I actually finish it all. I actually do that on purpose, because it forces me to consider a lot more possibilities along the way. There are a lot of questions that might be answered by looking at how the code is actually being used in parts that I haven’t read yet.

At any rate, one thing to note here is that I think that there is a distinct possibility that a crash after segment N +1 was written (and synced) but before segment N was done writing might undo the successful write for N+1. I’m not sure yet how this is used, so that is just something to keep in mind for now.

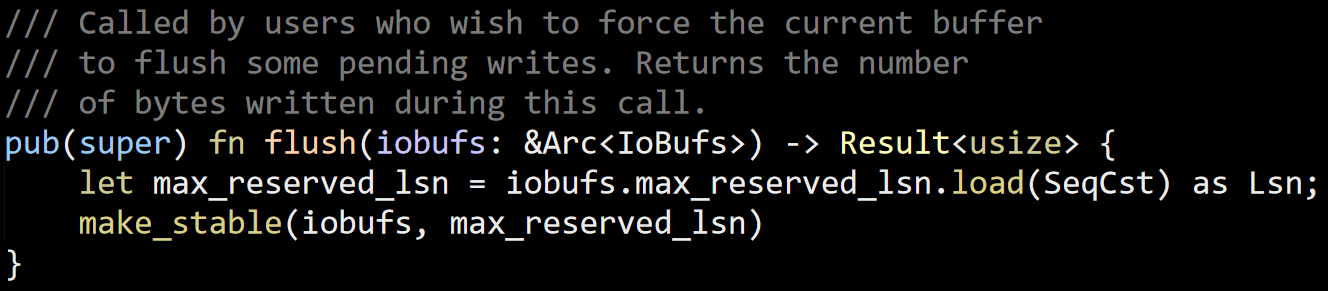

I managed to find this guy:

If you’ll recall, this is called on a timer to write the current in memory state.

The only other interesting thing in this file is:

This looks like it is racing with other calls on trying to write the current buffer. I’m not so sure what sealed means. I think that this is to prevent other threads from writing to the same buffer while you might be trying to write it out.

That is enough for now, it has gotten late again, so I’ll continue this in another post.

Comments

"I think that there is a distinct possibility that a crash after segment N +1 was written (and synced) but before segment N was done writing might undo the successful write for N+1"

Correct - otherwise we would lose atomic recovery. We allow buffers to be written out-of-order to avoid any head-of-line blocking on the ring-buffer of IO buffers.

Tyler, How often do you have parallel work here? I mean, multiple segment writes at the same time? Have you considered using direct I/O to avoid the

fsynccall? My results show that this is _expensive_, but direct I/O, especially if you can send the whole buffer as a single item, is much cheaper.It's not ideal, but it's also not a huge cost right now. When running with the async configurable, these writes all get punted to rayon and writing threads can continue without blocking, with a small throughput hit. on the slower SSDs I've measured it can take around 8ms sometimes to write and fsync 8mb segments. This only becomes problematic when all available IO buffers are sealed and waiting to be written to disk and threads trying to reserve space for a write have to wait.

O_DIRECT, linux kernel AIO, and io_uring are all very interesting, and I'm looking forward to seeing if they improve performance at this stage of the project. I'm expecting modest improvements, because high latency percentiles for certain tasks are driven by occasional hiccups with the various IO tasks. The main throughput limiter and latency cause at the latency percentiles below 99.9 are compute costs related to using naive standard rust data structures in a lot of places still.

There are so many low-hanging optimizations still laying around, it's nice to not feel very stuck. On a test machine with an intel 9900k I'm able to approach a million 10b key / 10b value writes per second, so we're doing OK for certain workloads despite being really naive in certain places still.

Tyler, I think you are being misled here by your hardware. In particular, it is very likely that you are going to need to consider cloud instances. On the cloud, I/O is a really constrained resources, and even SSD or NVMe instances on the cloud is going to suck really hard. Significantly slower than even what you'll consider to be poorly performing physical hardware.

Tyler, I think you are being misled here by your hardware. In particular, it is very likely that you are going to need to consider cloud instances. On the cloud, I/O is a really constrained resources, and even SSD or NVMe instances on the cloud is going to suck really hard. Significantly slower than even what you'll consider to be poorly performing physical hardware.

I've done some measurements on AWS M*s, C3's which showed that undesirable queuing wasn't happening due to fsync. I'm sure there's some busy neighbor and normal high latency arch stuff to watch out for, but with the current sled arch we seem to be able to avoid user threads in the read and write paths from being impacted. I can see how this is worse for you though because you mentioned in the last blog post that your system blocks async tasks until their associated writes are durable. I chose to avoid this from the beginning based on experiences managing a variety of systems where keeping queue depths low across a cluster, combined with replication, was a nice way to avoid various harmonic queuing effects through a whole topology. But both approaches are nice for different use cases and I'll probably add something similar down the line for event sourcing folks / latency insensitive high consistency loads etc...

Tyler, Note that your testing might suffer from burstable I/O. That is, in AWS in particular, you have 500 IOPS, but you have a budget of 3000 IOPS for a while, which can lead to great benchmarks, that fall over after a while

Comment preview