Distributed compare-exchange operations with RavenDB

RavenDB uses a consensus protocol to manage much of its distributed state. The consensus is used to ensure consistency in a distributed system and it is open for users as well. You can use this feature to enable some interesting scenarios.

The idea is that you can piggy back on RavenDB’s existing consensus engine to gain the ability allow you to create robust and consistent distributed operations. RavenDB exposes these operations using a pretty simple interface: compare-exchange.

At the most basic level, you have a key/value interface that you can make distributed atomic operations on, knowing that they are completely consistent. This is great, in abstract, but it s a bit hard to grasp without a concrete example.

Consider the following scenario. We have a bunch of support engineers, ready and willing to take on any support call that come. At the same time, an engineer can only a certain number of support calls. In order to handle this, we allow engineers to register when they are available to take a new support call. How would we handle this in RavenDB? Assuming that we wanted absolute consistency? An engineer may never be assigned too much work and work may never be lost. Assume that we need this to be robust in the face of network and node failure.

Here is how an engineer can register to the pool of available engineers.

The code above is very similar to how you would write multi-threaded code. You first get the value, then attempt

to do an atomic operation to swap the old value with the new one. If we are successful, the operation is done. If not, then

we retry. Concurrent calls to RegisterEngineerAvailability will race each other. One of them will succeed and the others

will have to retry.

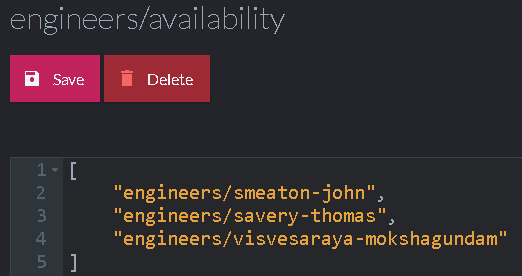

The actual data that we store in the compare exchange value in this case is an array. You can see an example of how that would look here:

Compare exchange values can be simple values (numbers, strings), arrays or even objects. Any value that can be represented

as JSON is valid there. However, the only operation that is allowed on a compare exchange value is a wholesale replacement.

The code above is only doing half of the job. We still need to be able to get an engineer to help us handle a support call. The code to complete this task is shown below:

The code for pulling an engineer from the pool is a bit more complex. Here we read the available engineers from the server. If there are none, we'll

wait a bit and try again. If there are available engineers we'll remove the first one and then try to update the value. This

can happen for multiple clients at the same time, so we check whatever our update was successful and only return the engineer

if our change was accepted.

Note that in this case we use two different modes to update the value. If there are still more engineers in the available pool, we'll just remove our engineer and update the value. But if our engineer is the last one, we'll delete the value

entirely. In either case, this is an atomic operation that will first check the index of the pre-existing value before

performing the write.

It is important to note that when using compare exchange values, you'll typically not act on read. In other words, in PullAvailableEngineer, even if we have an available engineer, we'll not use that knowledge until we successfully wrote the new value.

The whole idea with compare exchange values is that they give you atomic operation primitive in the cluster. So a typical

usage of them is always to try to do something on write until it is accepted, and only then use whatever value you read.

The acceptance of the write indicates the success of your operation and the ability to rely on whatever values you read.

However, it is important to note that compare exchange operations are atomic and independent. That means an operation

that modify a compare exchange value and then do something else needs to take into account that these would run in separate

transactions.

For example, if a client pull an engineer from the available pool but doesn't provide any work (maybe because the client

crashed) the engineer will not magically return to the pool. In such cases, the idle engineer should periodically check

that the pool still the username and add it back if it is missing.

Comments

In RegisterEngineerAvailability you don't seem to use the engineer parameter. Should it be added to the list before the put operation?

Is it possible to mix this within a regular ACID database transaction that does something with the engineer you just retrieved from the "compare exchange"?

We need to account for the possibility of something going wrong on the client-side right after removing the engineer from the list (application crashes, power outage, code bug, etc), and now the engineer would be lost forever

Andrew, Opps, correct, I fixed the demo.

Rodrigo, The answer is a bit complex. In 4.0, the answer to that is that this will be handled by a retry on the engineer every now and then, as mentioned in the psot. In 4.1, you can compose such operations with transactions on documents, yes.

Aren't you adding the engineer twice in RegisterEngineerAvailability() when creating a new CompareExchangeValue? Once in the initializer an then by Add()?

Tobi, Yes, correct. Fixed now.

Comment preview