I was talking with a developer about their system architecture and they mentioned that they are going through some complexity at the moment. They are changing their architecture to support higher scaling needs. Their current architecture is fairly simple (single app talking to a database), but in order to handle future growth, they are moving to a distributed micro service architecture. After talking with the dev for a while, I realized that they were in a particular industry that had a hard barrier for scale.

I’m not sure how much I can say, so let’s say that they are providing a platform to setup parties for newborns in a particular country. I went ahead and checked how many babies you had in that country, and the number has been pretty stable for the past decade, sitting on around 60,000 babies per year.

Remember, this company provide a specific service for newborns. And that service is only applicable for that country. And there are about 60,000 babies per year in that country. In this case, this is the time to do some math:

- We’ll assume that all those births happen on a single month

- We’ll assume that 100% of the babies will use this service

- We’ll assume that we need to handle them within business hours only

- 4 weeks x 5 business days x 8 business hours = 160 hours to handle 60,000 babies

- 375 babies to handle per hour

- Let’s assume that each baby requires 50 requests to handle

- 18,750 requests / hour

- 312 requests / minute

- 5 requests / second

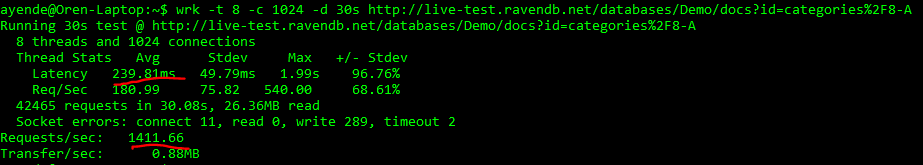

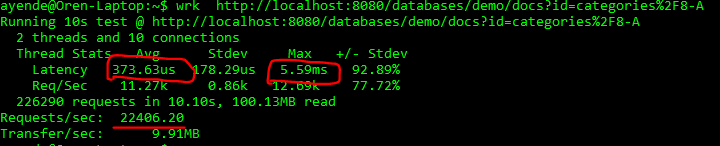

In other words, given the natural limit of their scaling (number of babies per year), and using very pessimistic accounting for the load distribution, we get to a number of requests to process that is utterly ridiculous.

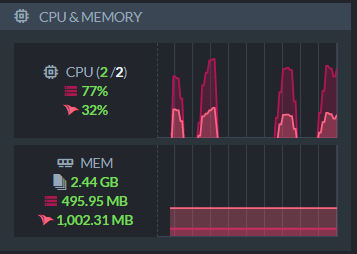

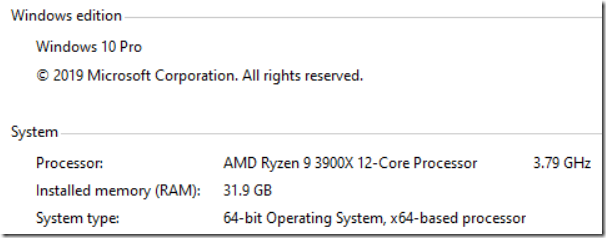

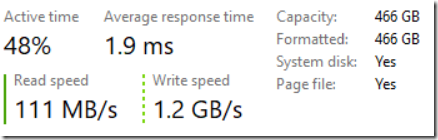

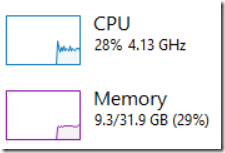

It would be hard to not handle this properly on any server you care to name. In fact, you can get a machine under 150$ / month that has 8 cores. That gives you a core per requests per second, with 3 to spare.

Even if we have to deal with spikes of 50 requests / second. Any reasonable server ( the < 150% / month I mentioned) should be able to easily handle this.

About the only way for this system to get additional load is if there is a population explosion, at which point I assume that the developers will be busy handling nappies, not watching the CPU utilization.

For certain type of applications, there is a hard cap of what load you can be expected to handle. And you should absolutely take advantage of this. The more stuff you can not do, the better you are. And if you can make reasonable assumptions about your load, you don’t need to go crazy.

Simpler architecture means faster time to market, meaning that you can actually deliver value, rather than trying to prepare for the Babies’ Apocalypse.